Curatorial Statement

Contemporary Apprenticeship: Synthesizing Old and New (excerpt)

By Daniel Garretson

Apprenticeship, the world over, is a time-tested method of communicating knowledge through immersion in the specific practice of a particular artist or workshop. Over the course of history apprenticeships have taken innumerable forms and continue to evolve relative to the context in which they are embedded. How, then, do our present social/political/technological circumstances shape contemporary apprenticeships; and what, if anything, is particular to a contemporary American apprenticeship? It was these questions that initiated the exhibition The American Apprentice at the Red Lodge Clay Center, and in effect, provoked me to reflect on my own experiences during a three-year apprenticeship with Mark Shapiro. Having completed my apprenticeship several years ago and being a current graduate student at Alfred University has lent some perspective to these reflections. In sharing some of these experiences I hope to contribute to an understanding of the evolution of the American apprenticeship system.

In the United States apprenticeships are no longer aimed at teaching a particular style of making to be passed down by successive generations. For better or worse, contemporary American culture values the new, unique, and individual. Successful apprenticeships, therefore, must not only teach the essential skills demanded of a particular craft, but also how to develop an individual voice as an artist and the ability to clearly articulate the meaning of one’s work. Perhaps most importantly is the means to make one’s voice heard within the current economic paradigm in which we all operate.

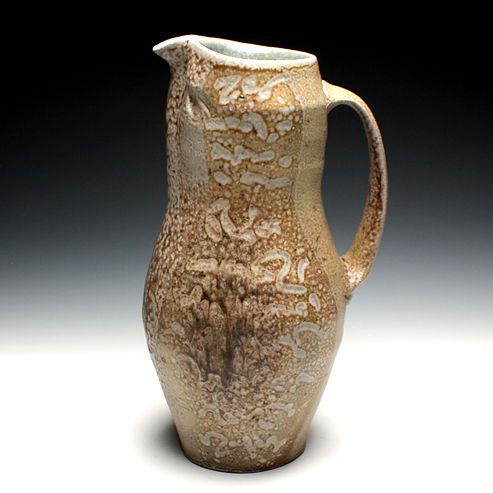

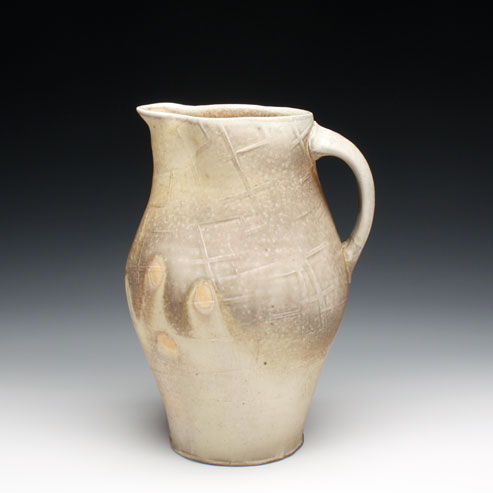

During my apprenticeship [with Mark Shapiro] I witnessed first hand the diverse methods that Mark employed to make a living. Sending pots to galleries both international and domestic, travelling far and wide teaching workshops and giving lectures, engaging in writing and editing projects, are to name but a few. The digital revolution has fundamentally changed the marketplace. The contemporary potter who ignores these changes does so at their own peril. Making pots is no longer enough; taking digital images, website design, maintaining online galleries, and social networking are but a few of the skills demanded by the market place. The contemporary potter may spend just as much time behind a computer screen as at the potter’s wheel. It is not possible to retreat to an earlier, perhaps simpler time; rather, it is necessary to synthesize essential elements of both old and new.

To be sure, contemporary apprenticeships have much in common with apprenticeships of two thousand years ago, remaining a vital format for learning and communication. However, time never stands still and for apprenticeships to remain relevant they must reinterpret the questions they are attempting to answer. The unique models established by Mark Shapiro, Chris Gustin, Silvie Granatelli, Victoria Christen and Simon Levin testify to the successful ways in which craft culture is responding to current circumstances regionally, nationally, and globally.